plagued by longing 2024 - ongoing

plagued by longing

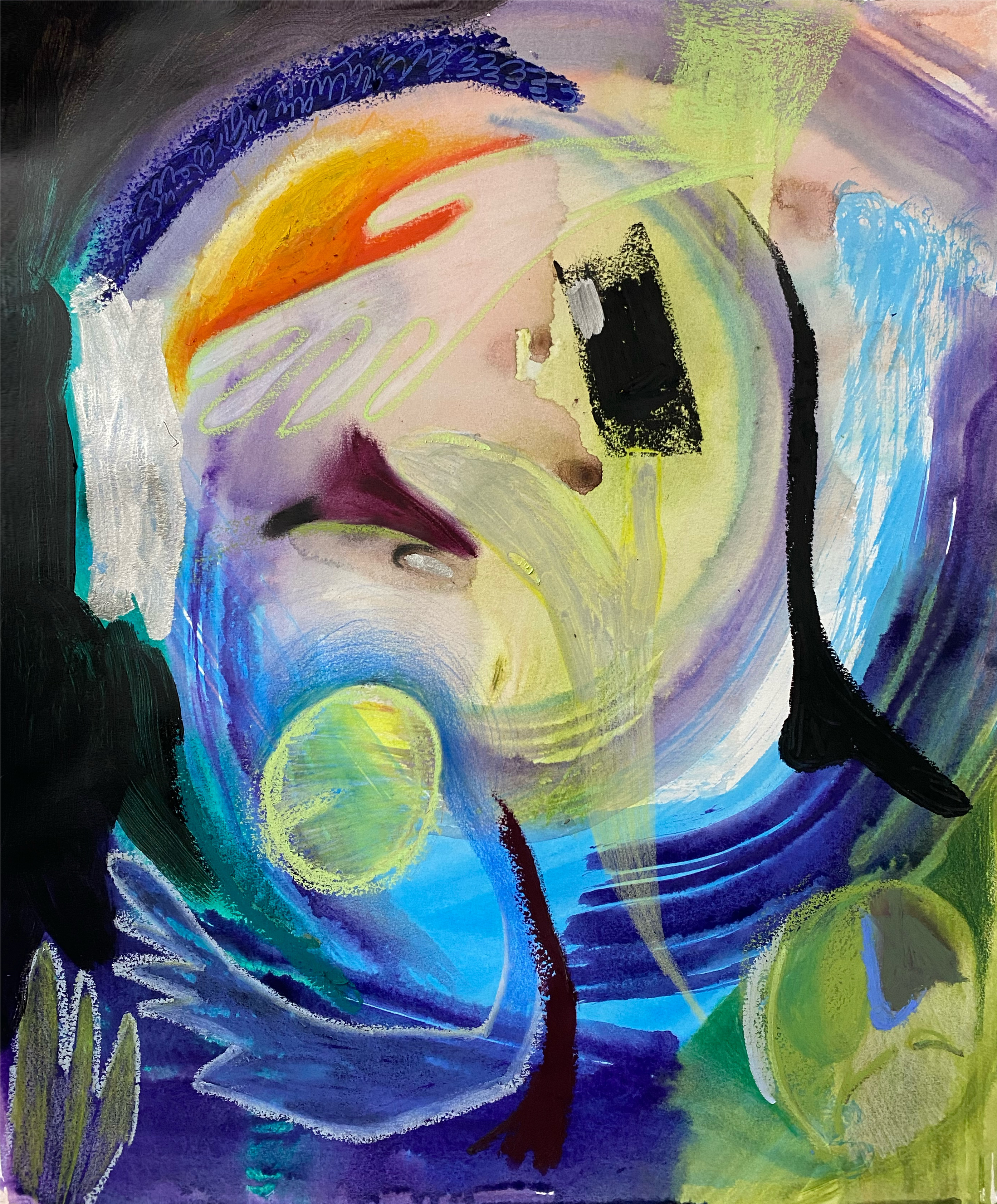

In 2004, my father survived a heart attack and seizure, undergoing a near-death experience (NDE) during the ten minutes he was clinically dead. This event caused permanent short-term memory loss, subsequently leading to dementia. The work begins with his NDE account, a repeated narrative that grounds him amidst confusion. The story has been a conduit to traverse his memories: growing up in the Philippines, immigrating to America, and his longing to return to our motherland. The lapse in his memories mirrors the blurry precolonial histories in the Philippines, overshadowed by colonial influence.

This body of work follows my father's narrative to drive my investigations of recovering my family’s history, while contextualizing it within the colonial history of the Philippines. Storytelling is used as a making process that pulls from a lived experience. Through retelling, elements shift and change, transforming the narrative into something different: a complicated record that fuses the past and the present via the storyteller. As my father's dementia affects his memories, through recounting his experiences, nuances evolve depending on his current state, tangling the past, present, and future within the narrative.

Rather than simply verbalizing the tale, I engage in a somatic process, locating tensions within my body that have absorbed the story. I then transform materials through collapsing and extending them into forms that echo my body's repository of inherited experiences.

Variations of this series have been featured with Feia Gallery, Luis De Jesus Los Angeles, and at DMST Atelier.

Article: How artistic research preserves cultural memory and care by Debra Herrick

Photo documentation by Matt Savitsky and Möe Wakai.

(Right-click open in new tab to see Hi-Res images)

In 2004, my father survived a heart attack and seizure, undergoing a near-death experience (NDE) during the ten minutes he was clinically dead. This event caused permanent short-term memory loss, subsequently leading to dementia. The work begins with his NDE account, a repeated narrative that grounds him amidst confusion. The story has been a conduit to traverse his memories: growing up in the Philippines, immigrating to America, and his longing to return to our motherland. The lapse in his memories mirrors the blurry precolonial histories in the Philippines, overshadowed by colonial influence.

This body of work follows my father's narrative to drive my investigations of recovering my family’s history, while contextualizing it within the colonial history of the Philippines. Storytelling is used as a making process that pulls from a lived experience. Through retelling, elements shift and change, transforming the narrative into something different: a complicated record that fuses the past and the present via the storyteller. As my father's dementia affects his memories, through recounting his experiences, nuances evolve depending on his current state, tangling the past, present, and future within the narrative.

Rather than simply verbalizing the tale, I engage in a somatic process, locating tensions within my body that have absorbed the story. I then transform materials through collapsing and extending them into forms that echo my body's repository of inherited experiences.

Variations of this series have been featured with Feia Gallery, Luis De Jesus Los Angeles, and at DMST Atelier.

Article: How artistic research preserves cultural memory and care by Debra Herrick

Photo documentation by Matt Savitsky and Möe Wakai.

(Right-click open in new tab to see Hi-Res images)

I’m Still Dancing

This ongoing series draws from intimate dance gatherings that emerged in the wake of the tumultuous year 2020. These gatherings offered a form of solace, using movement as a way to process heightened stress, grief, and uncertainty. This installation transforms these ephemeral moments into a physical space for reflection and communal memory through kinetic sculptures, immersive sound, and video. Though the project initially was in response to 2020, the same issues continue to persist today.

At the heart of this project is an installation featuring a large dance floor embedded with low-frequency vibrations from iconic 90s and 2000s dance tracks. As the bass pulses, oversized shoe sculptures awkwardly propel across the floor, transforming sonic rhythms into physical expressions of release and resistance. Etched drawings on the concrete-tiled surfaces and resin wall panels record these movements, preserving the traces of past dance gatherings. The almost recognizable songs are paired with a harsh jackhammering sound, reminding the viewer that these moments of release still exist within governed architectures.

Iterations of this series have been exhibited with Feia Gallery and Luis De Jesus Los Angeles.

Photo documentation by Matt Savitsky, Möe Wakai, and Luis De Jesus Los Angeles.

(Right-click open in new tab to see Hi-Res images)

This ongoing series draws from intimate dance gatherings that emerged in the wake of the tumultuous year 2020. These gatherings offered a form of solace, using movement as a way to process heightened stress, grief, and uncertainty. This installation transforms these ephemeral moments into a physical space for reflection and communal memory through kinetic sculptures, immersive sound, and video. Though the project initially was in response to 2020, the same issues continue to persist today.

At the heart of this project is an installation featuring a large dance floor embedded with low-frequency vibrations from iconic 90s and 2000s dance tracks. As the bass pulses, oversized shoe sculptures awkwardly propel across the floor, transforming sonic rhythms into physical expressions of release and resistance. Etched drawings on the concrete-tiled surfaces and resin wall panels record these movements, preserving the traces of past dance gatherings. The almost recognizable songs are paired with a harsh jackhammering sound, reminding the viewer that these moments of release still exist within governed architectures.

Iterations of this series have been exhibited with Feia Gallery and Luis De Jesus Los Angeles.

Photo documentation by Matt Savitsky, Möe Wakai, and Luis De Jesus Los Angeles.

(Right-click open in new tab to see Hi-Res images)

Smoking in the Garden at Phase Gallery, Los Angeles

Smoking in the Garden explores folklore from stories passed down through Kim’s mother, investigating how an oral narrative can transform trauma into power. These works express how her body and lived experiences digest intimacy while employing memory, in all of its slipperiness, to explore interpersonal power dynamics. Using the trace of history as a key element in her work, Kim's material practice combines sculpture, drawing, and painting to investigate residual tensions built up to the present. This latest body of work is a form of sincere and sentimental inscription, describing the love entwined in a mother-daughter relationship and the postcolonial identity in all its cryptic layers.

Love is traditionally something that must be upkept, where stains can both hide and reveal what is lacking in a relationship. From the repeated performance of this oral history, meaning is brought forth from the realm of the imaginary through material play. Kim herself acknowledges that each story is interlaced with familial and colonial trauma - an inheritance she is conscious of as the daughter of immigrants. Walking through those shadows as an act of care and remembrance, Kim uses her material process to ritualize these narrative moments into a healing practice. To stand with her shadow self and the shadows that have come before her time, Kim gives power to the absent: what isn't visible, what may be powerless, and what cannot be easily defined.

Simulating the oral narrative recited by her mother, Kim uses repeated visuals that shift in scale and move through the planes of a surface. Forms from this series collapse in certain areas and expand in others, functioning both as supporting tissues and objects that dominate space. Punctures on surfaces disintegrate the visible membrane between here and there. Much like recalling the past, the textures of the surface are gooey, thick, layered, slimy, and agitated. The work contends with history outside the conventions of a linear timeline. Color becomes a connotative device to evoke complicated moments in a relationship, like the operation of warmth and intensity on one side and rejection or harm on the other.

The show takes its title from Kim's middle name Fumar, inherited from her mother, which translates from Spanish to English to smoke. Its amorphous state of being is the product of some material cannibalization into a gas – in most cultures, it can purify or contaminate bodies. It is a verb with affect, agency, and change, all inherent in its meaning. In Smoking in the Garden, Kim presents a world arrested between fiction and history, here and there, self and other.

Written by Liz Stringer is an artist and writer living in Los Angeles

Additional accompanying Texts: Reflections on the Ashtray by Lawrence Chit and Letter to Kim Garcia from Liz Stringer

solo exhibition | photo documentation by Yubo Dong ofstudio photography

(Right-click open in new tab to see Hi-Res images)

Smoking in the Garden explores folklore from stories passed down through Kim’s mother, investigating how an oral narrative can transform trauma into power. These works express how her body and lived experiences digest intimacy while employing memory, in all of its slipperiness, to explore interpersonal power dynamics. Using the trace of history as a key element in her work, Kim's material practice combines sculpture, drawing, and painting to investigate residual tensions built up to the present. This latest body of work is a form of sincere and sentimental inscription, describing the love entwined in a mother-daughter relationship and the postcolonial identity in all its cryptic layers.

Love is traditionally something that must be upkept, where stains can both hide and reveal what is lacking in a relationship. From the repeated performance of this oral history, meaning is brought forth from the realm of the imaginary through material play. Kim herself acknowledges that each story is interlaced with familial and colonial trauma - an inheritance she is conscious of as the daughter of immigrants. Walking through those shadows as an act of care and remembrance, Kim uses her material process to ritualize these narrative moments into a healing practice. To stand with her shadow self and the shadows that have come before her time, Kim gives power to the absent: what isn't visible, what may be powerless, and what cannot be easily defined.

Simulating the oral narrative recited by her mother, Kim uses repeated visuals that shift in scale and move through the planes of a surface. Forms from this series collapse in certain areas and expand in others, functioning both as supporting tissues and objects that dominate space. Punctures on surfaces disintegrate the visible membrane between here and there. Much like recalling the past, the textures of the surface are gooey, thick, layered, slimy, and agitated. The work contends with history outside the conventions of a linear timeline. Color becomes a connotative device to evoke complicated moments in a relationship, like the operation of warmth and intensity on one side and rejection or harm on the other.

The show takes its title from Kim's middle name Fumar, inherited from her mother, which translates from Spanish to English to smoke. Its amorphous state of being is the product of some material cannibalization into a gas – in most cultures, it can purify or contaminate bodies. It is a verb with affect, agency, and change, all inherent in its meaning. In Smoking in the Garden, Kim presents a world arrested between fiction and history, here and there, self and other.

Written by Liz Stringer is an artist and writer living in Los Angeles

Additional accompanying Texts: Reflections on the Ashtray by Lawrence Chit and Letter to Kim Garcia from Liz Stringer

solo exhibition | photo documentation by Yubo Dong ofstudio photography

(Right-click open in new tab to see Hi-Res images)

she has her mother’s eyes

In 2019, I began a series exploring folklore passed down by my mother, delving into its significance as a fantastical origin tale of her family history. This creative endeavor also served as a cathartic process, addressing trauma spanning our mother-daughter bond, familial ties, and the history of the Philippines.

Spain's publication of the "Catálogo alfabético de apellidos" in 1849 established a system for selecting last names. Indigenous Filipinos chose surnames alphabetically, yet I discovered no mention of Fumar, my mother's maiden name, within the document. Although it likely deviated slightly, it intrigued me due to its translation as "to smoke.”

The interplay between smoke and the surname mirrors my mother's ever-evolving narrative. The name itself encompasses the entire story, reflecting its transformations, adaptations, and reconstructions to convey strength while still bearing the imprints of trauma. This ongoing series explores intergenerational trauma and the complex dynamics of power and wounds.

This series led up to a final solo exhibition at Phase Gallery Los Angeles on May 13, 2023.

(Right-click open in new tab to see Hi-Res images)

In 2019, I began a series exploring folklore passed down by my mother, delving into its significance as a fantastical origin tale of her family history. This creative endeavor also served as a cathartic process, addressing trauma spanning our mother-daughter bond, familial ties, and the history of the Philippines.

Spain's publication of the "Catálogo alfabético de apellidos" in 1849 established a system for selecting last names. Indigenous Filipinos chose surnames alphabetically, yet I discovered no mention of Fumar, my mother's maiden name, within the document. Although it likely deviated slightly, it intrigued me due to its translation as "to smoke.”

The interplay between smoke and the surname mirrors my mother's ever-evolving narrative. The name itself encompasses the entire story, reflecting its transformations, adaptations, and reconstructions to convey strength while still bearing the imprints of trauma. This ongoing series explores intergenerational trauma and the complex dynamics of power and wounds.

This series led up to a final solo exhibition at Phase Gallery Los Angeles on May 13, 2023.

(Right-click open in new tab to see Hi-Res images)