Smoking in the Garden at Phase Gallery, Los Angeles

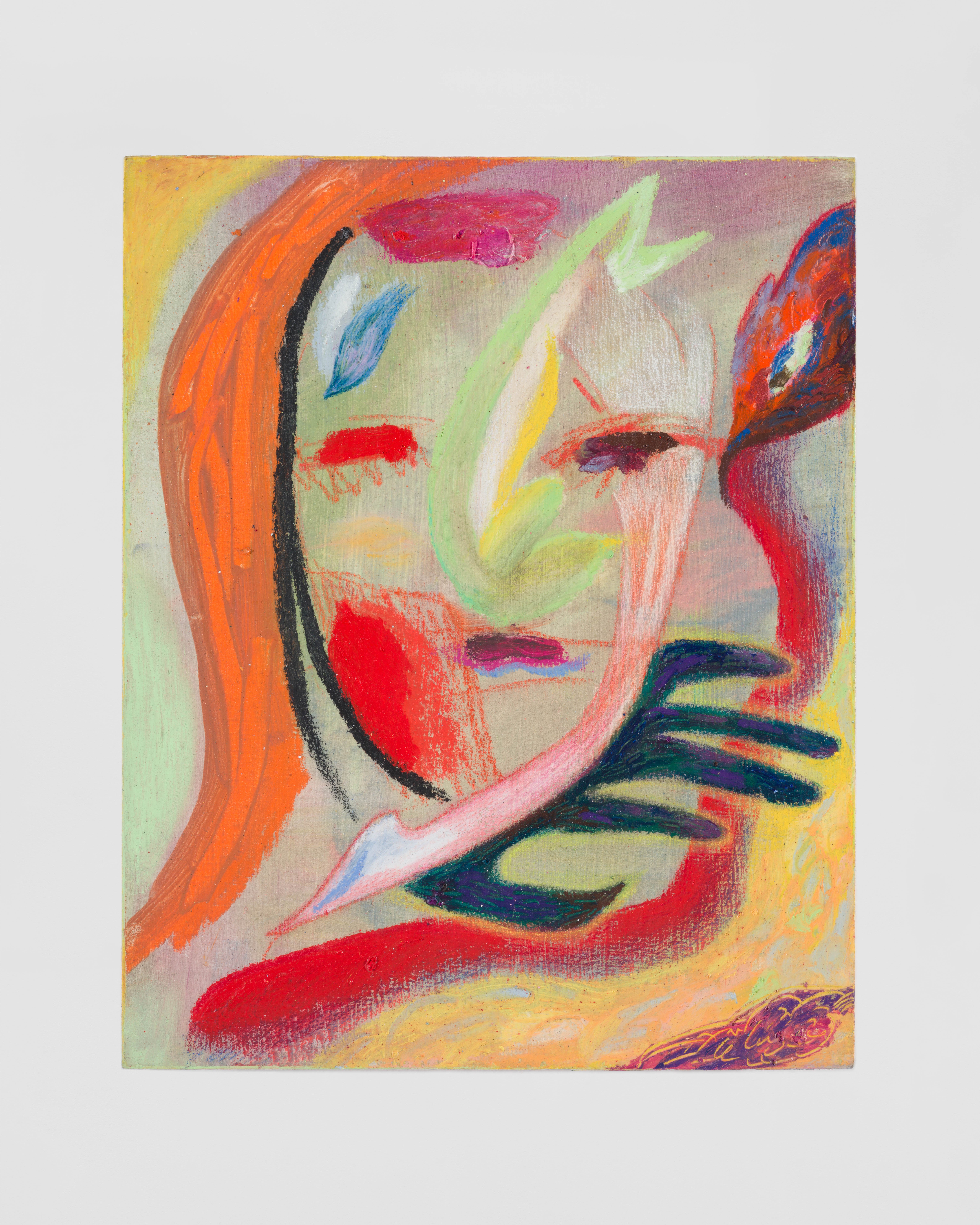

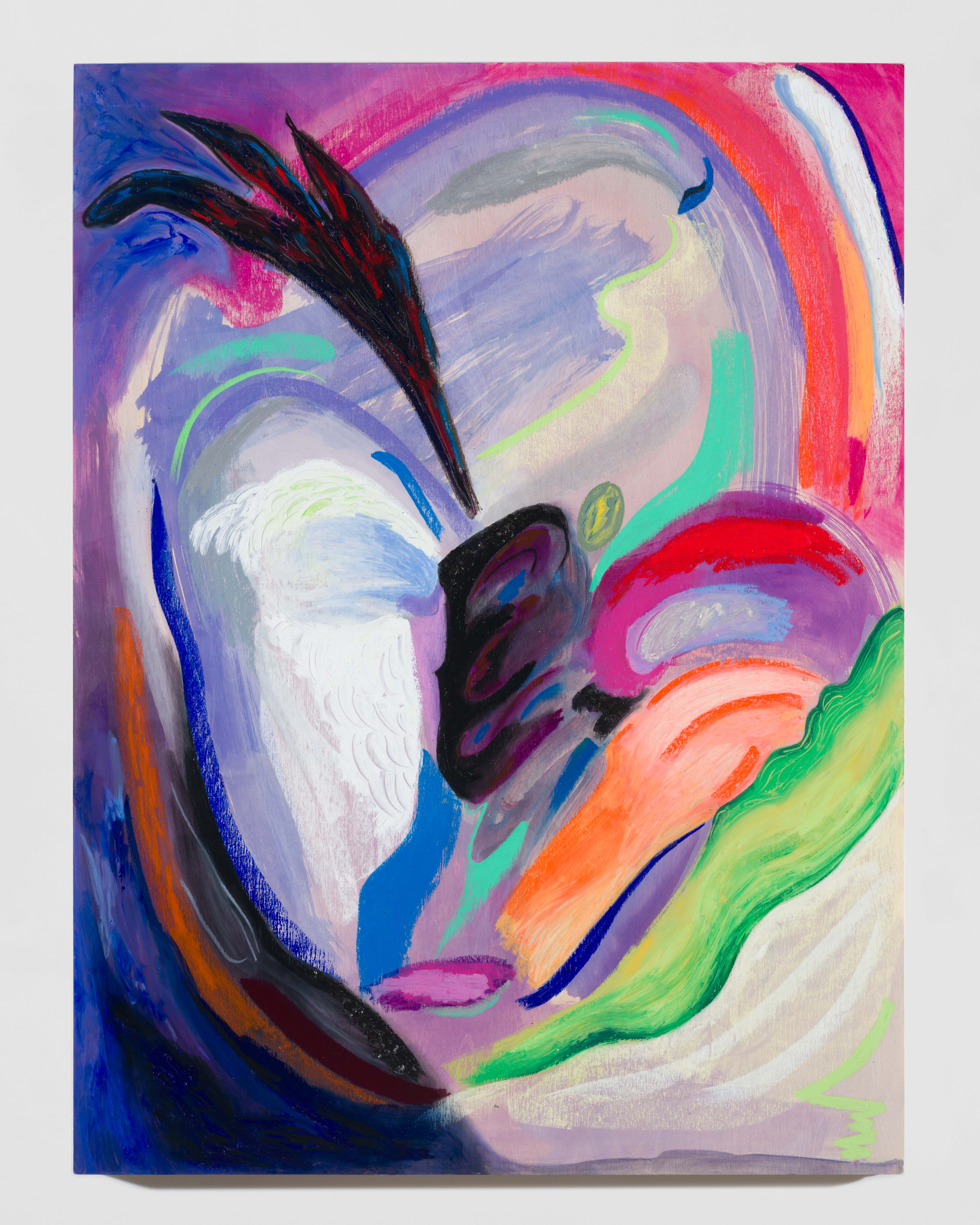

Smoking in the Garden explores folklore from stories passed down through Kim’s mother, investigating how an oral narrative can transform trauma into power. These works express how her body and lived experiences digest intimacy while employing memory, in all of its slipperiness, to explore interpersonal power dynamics. Using the trace of history as a key element in her work, Kim's material practice combines sculpture, drawing, and painting to investigate residual tensions built up to the present. This latest body of work is a form of sincere and sentimental inscription, describing the love entwined in a mother-daughter relationship and the postcolonial identity in all its cryptic layers.

Love is traditionally something that must be upkept, where stains can both hide and reveal what is lacking in a relationship. From the repeated performance of this oral history, meaning is brought forth from the realm of the imaginary through material play. Kim herself acknowledges that each story is interlaced with familial and colonial trauma - an inheritance she is conscious of as the daughter of immigrants. Walking through those shadows as an act of care and remembrance, Kim uses her material process to ritualize these narrative moments into a healing practice. To stand with her shadow self and the shadows that have come before her time, Kim gives power to the absent: what isn't visible, what may be powerless, and what cannot be easily defined.

Simulating the oral narrative recited by her mother, Kim uses repeated visuals that shift in scale and move through the planes of a surface. Forms from this series collapse in certain areas and expand in others, functioning both as supporting tissues and objects that dominate space. Punctures on surfaces disintegrate the visible membrane between here and there. Much like recalling the past, the textures of the surface are gooey, thick, layered, slimy, and agitated. The work contends with history outside the conventions of a linear timeline. Color becomes a connotative device to evoke complicated moments in a relationship, like the operation of warmth and intensity on one side and rejection or harm on the other.

The show takes its title from Kim's middle name Fumar, inherited from her mother, which translates from Spanish to English to smoke. Its amorphous state of being is the product of some material cannibalization into a gas – in most cultures, it can purify or contaminate bodies. It is a verb with affect, agency, and change, all inherent in its meaning. In Smoking in the Garden, Kim presents a world arrested between fiction and history, here and there, self and other.

Written by Liz Stringer is an artist and writer living in Los Angeles

Additional accompanying Texts: Reflections on the Ashtray by Lawrence Chit and Letter to Kim Garcia from Liz Stringer

solo exhibition | photo documentation by Yubo Dong ofstudio photography

(Right-click open in new tab to see Hi-Res images)

Smoking in the Garden explores folklore from stories passed down through Kim’s mother, investigating how an oral narrative can transform trauma into power. These works express how her body and lived experiences digest intimacy while employing memory, in all of its slipperiness, to explore interpersonal power dynamics. Using the trace of history as a key element in her work, Kim's material practice combines sculpture, drawing, and painting to investigate residual tensions built up to the present. This latest body of work is a form of sincere and sentimental inscription, describing the love entwined in a mother-daughter relationship and the postcolonial identity in all its cryptic layers.

Love is traditionally something that must be upkept, where stains can both hide and reveal what is lacking in a relationship. From the repeated performance of this oral history, meaning is brought forth from the realm of the imaginary through material play. Kim herself acknowledges that each story is interlaced with familial and colonial trauma - an inheritance she is conscious of as the daughter of immigrants. Walking through those shadows as an act of care and remembrance, Kim uses her material process to ritualize these narrative moments into a healing practice. To stand with her shadow self and the shadows that have come before her time, Kim gives power to the absent: what isn't visible, what may be powerless, and what cannot be easily defined.

Simulating the oral narrative recited by her mother, Kim uses repeated visuals that shift in scale and move through the planes of a surface. Forms from this series collapse in certain areas and expand in others, functioning both as supporting tissues and objects that dominate space. Punctures on surfaces disintegrate the visible membrane between here and there. Much like recalling the past, the textures of the surface are gooey, thick, layered, slimy, and agitated. The work contends with history outside the conventions of a linear timeline. Color becomes a connotative device to evoke complicated moments in a relationship, like the operation of warmth and intensity on one side and rejection or harm on the other.

The show takes its title from Kim's middle name Fumar, inherited from her mother, which translates from Spanish to English to smoke. Its amorphous state of being is the product of some material cannibalization into a gas – in most cultures, it can purify or contaminate bodies. It is a verb with affect, agency, and change, all inherent in its meaning. In Smoking in the Garden, Kim presents a world arrested between fiction and history, here and there, self and other.

Written by Liz Stringer is an artist and writer living in Los Angeles

Additional accompanying Texts: Reflections on the Ashtray by Lawrence Chit and Letter to Kim Garcia from Liz Stringer

solo exhibition | photo documentation by Yubo Dong ofstudio photography

(Right-click open in new tab to see Hi-Res images)